![]()

Something about

Antibodies are our molecular watchdogs, waiting and watching for viruses, bacteria and other unwelcome visitors. Antibodies circulate in the blood, scrutinizing every object that they touch.

When they find an unfamiliar, foreign object, they bind tightly to its surface. In the case of viruses, a coating of bound antibodies may be enough to block infection.

Antibodies alone, however, are no match for bacteria. When antibodies bind to a bacterial surface, they act as markers alerting the other powerful defensive mechanisms available in the immune system.

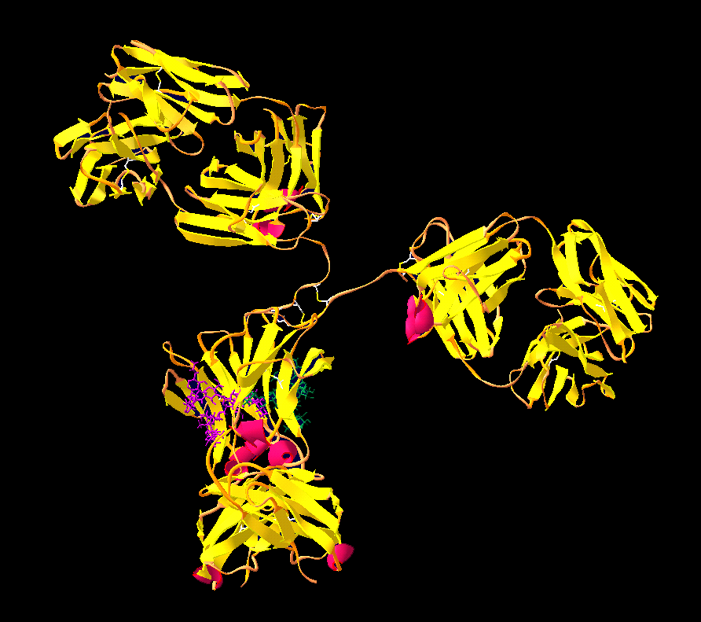

- Cartoon representation of

the

Immunoglobin G

- Colors indicates a structure

elements:

- helices

- strands

- loops

- disulfide bonds

Getting a Grip

Antibodies, and many of the other molecules used in the immune system, have a distinctive shape. Typically, they are composed of several flexible arms with binding sites at the end of each one. This make perfect sense: since antibodies do not know in advance what attackers they might be fighting, they keep their options open. The flexible arms allow the binding sites to work together, grabbing with both arms onto targets with different overall shapes. The antibody shown here, from PDB entry 1igt, has two binding sites, at the tips of the two arms extending right and left at the top. Notice the thin, flexible chains that connect these arms to the central domain at the bottom. Some antibodies have longer flexible linkers connecting the arms together, allowing them even more latitude when finding purchase on a surface. Other antibodies have four or ten binding sites, so each contact can be weaker and still allow the whole antibody to bind firmly.